I’m an American Jew, and this year the High Holy Days of my religion have a special, and terrible, meaning for me. Another year of violence in the Middle East has brought tragedy to millions, and contributed to a surge in anti-semitism around the world. Last Monday, I found some comfort in the company of others who feel, as I do, that our community should mark this Day of Atonement with more than personal acknowledgement of what we have done wrong.

A year after a vicious Hamas attack on Israeli civilians turned long-simmering violence into open warfare, a couple of thousand non-Zionist Jews and our allies gathered in the Boston Garden. We met to grieve — not only for the more than 1200 Israelis killed on that day, and the hundreds kidnapped, but for the tens of thousands of Palestinians killed in the bloody year since then, and for the Lebanese who are now also under Israeli attack. The event was organized by IfNotNow, a group devoted to ending American support for Israeli apartheid and aggression toward Palestinians.

Late on the damp Monday afternoon of that sad anniversary, before most of the crowd showed up, a young rabbinical student led us through an ancient Jewish ritual called Tashlikh. This ceremony is performed during the “Days of Awe” between Rosh HaShanah – the Jewish New Year – and Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. One symbolically casts off one’s sins by throwing something in flowing water to be washed away. Usually people throw bread crumbs, but out of concern for the fish in the pond, we threw pebbles or dead leaves instead. The pond water wasn’t washing anything away, which also seemed symbolic to me.

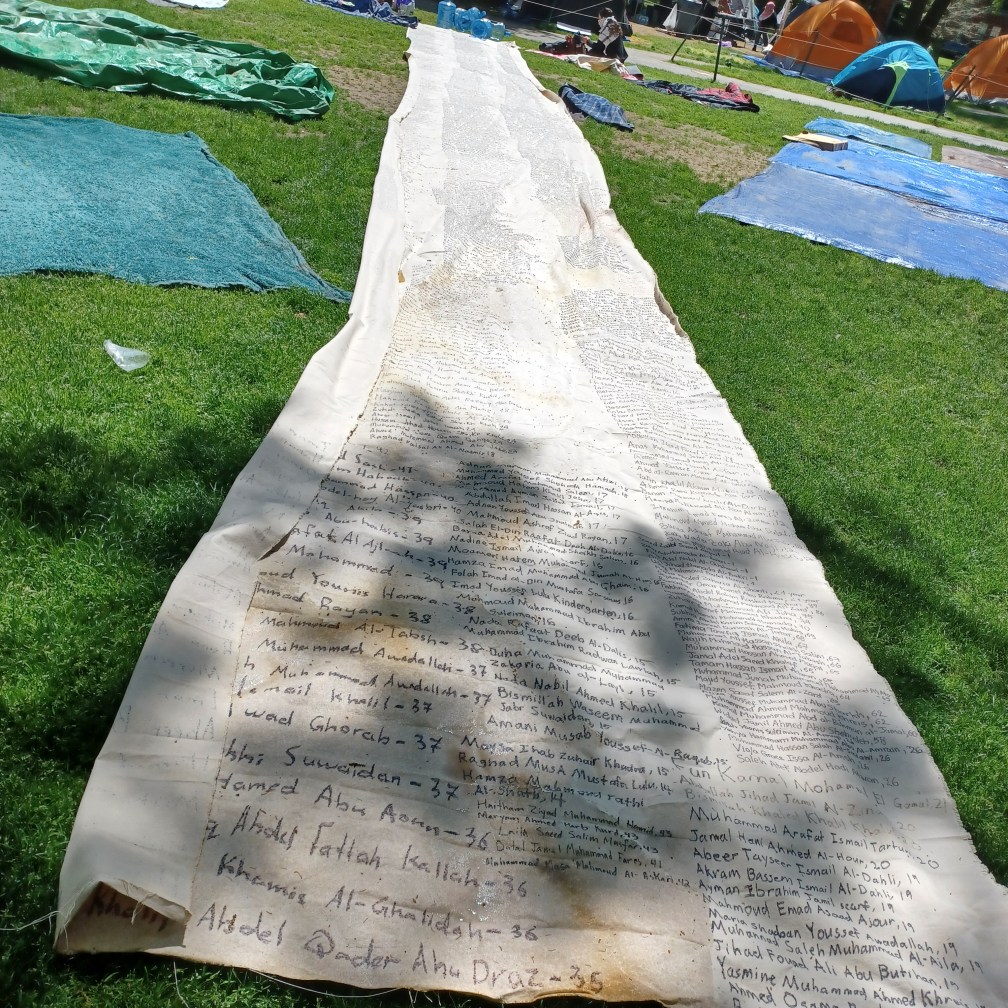

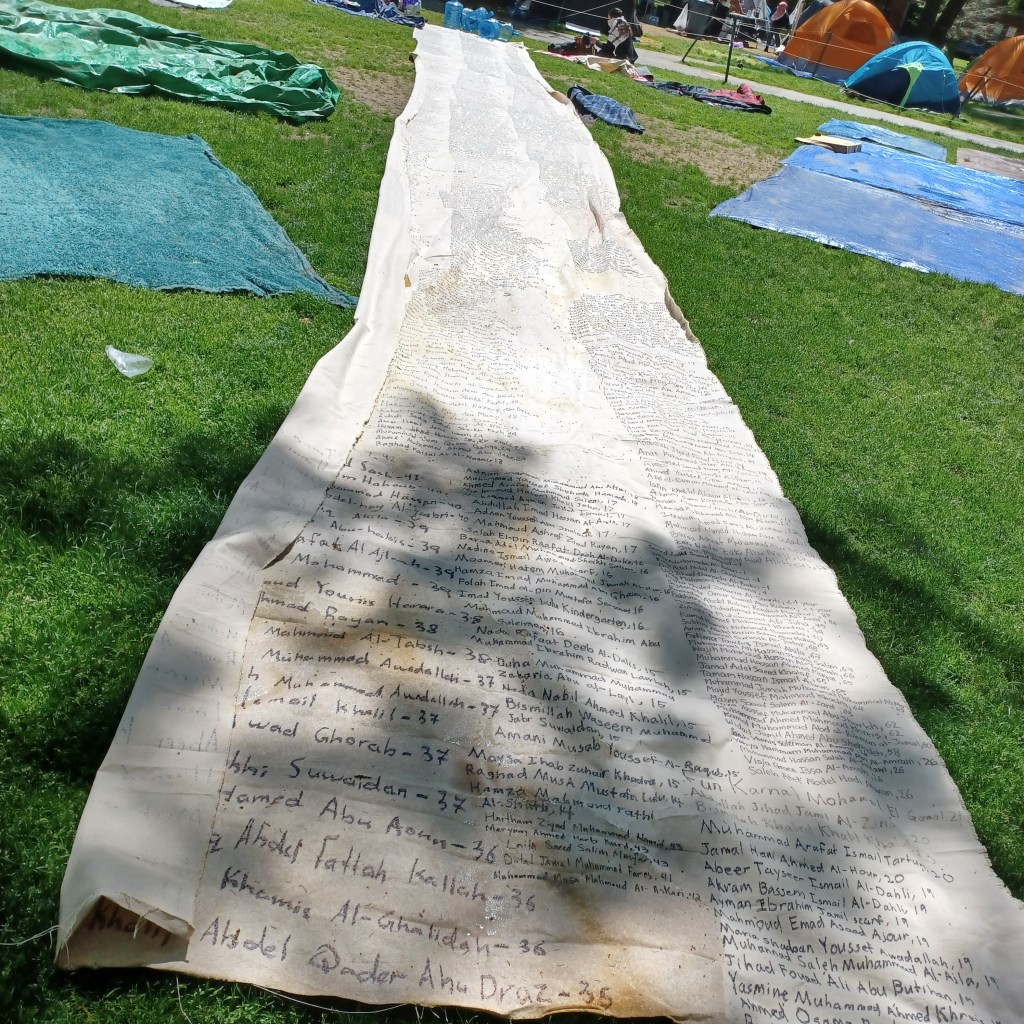

The theme of the main event was “Every life is a universe”. Speakers included Rep. Ayanna Pressley, Rabbi Toba Spitzer, Imam Ahmad Barry, and Rakeea Chesick Gordis. That young woman gave eloquent testimony to losing close friends and family members during the Gaza war, including both Israelis and Palestinians. She spoke of drowning in grief, feeling overwhelmed by waves of it. Again and again, the speakers insisted: Jews cannot be safe if Palestinians are not free.

After an hour of speeches, prayers, and songs, rain began to drip through the trees. Mosquitos emerged from the mist over the pond to ensure our discomfort. Considering the suffering we were there to commemorate, nobody complained. At one point, volunteers handed out small strips of cloth we were to rip, as a sign of mourning, and attach to our clothes.

October 12 is the Day of Atonement in the current year 5785 of the Hebrew calendar. I believe that American Jews have a lot to atone for. I am not refering to personal sins; Jews are no more or less hateful, thoughtless, or selfish than anybody else. I mean the Jewish community as a whole. For the most part, we have supported Israel for the 76 years of its existence, no matter what it did. We have pressured the US to continue sending more than $3 billion a year in military assistance to Israel, and ignored what Israel did with all those weapons.

Ever since the Holocaust killed six million Jews in Europe and the Nakba displaced three-quarters of a million Palestinians in Israel, both sides have committed too many atrocities to list. The difference is that American weapons have turned the Jewish state from David into Goliath. Israel has become a paragon of military might. Nearly all of its people are or have been soldiers. They believe they are fighting for survival, which excuses all their violence as self-defense.

According to the United Nations, from 2008 through 2020, 5590 Palestinians were killed in the ongoing hostilities, compared to 251 Israelis. There are many conflicting estimates of the casualties since the founding of Israel in 1948, but on one thing they all agree. Far more Palestinians have died than Israelis. This conflict is deeply lopsided, and not only in lives lost. The longer it goes on, the more territory originally set aside for a Palestinian state disappears into Israeli hands. Even the rubble that was Gaza is likely to get rebuilt into beach towns for Jewish tourists.

Now it seems that many American Jews have decided to drop their indifference to religion and rejoin the Jewish community. During most wars, previously apolitical people tend to rally around the flag. This is “my country, right or wrong” time. Jews everywhere have been taught to believe that Israel, and not the Torah, is the central element of our religion. In many ways, Israel has become our religion.

After 9/11, the US squandered the world’s sympathy by starting two completely unnecessary and unprovoked wars. Instead of hunting down the gang of Saudi terrorists that bombed the World Trade Center, we invaded and occupied Afghanistan and then Iraq. We killed hundreds of thousands, and made millions homeless. Now Israel has squandered the sympathy it garnered after the Hamas attack by bombing the millions of Palestinians it holds captive behind walls and military checkpoints in Gaza and the West Bank. Most of those who survive are now homeless, and many are starving.

Zionist Jews, and most Israelis, believe that this violence is justified because it’s the only way to destroy the criminal gang that is Hamas. Yet this policy is doomed to fail. Violence begets violence. Every time an Israeli bomb kills someone, Hamas can recruit more members from among the people who loved them. Zionists blame Hamas for all the destruction on both sides, just as the most extreme pro-Palestinians blame it entirely on Israel’s decades of oppression and occupation.

The truth is that there is plenty of blame to go around. So long as we find war acceptable, we all must share the blame for the loss of so many irreplaceable universes. I am grateful to IfNotNow for giving us a chance to start the new year by acknowledging our part in the ongoing crime of mass murder. May the year to come bring a ceasefire, and healing to all who suffer. We must make peace. If not now, then when?