Let’s deal in oversimplifications for this argument. Imagine an extremist Christian man and an extremist Muslim man talking about their beliefs in a living room somewhere. Their discussion grows more and more heated, and, depending on the men’s temperaments, might even come to blows.

Meanwhile, their wives are in the kitchen, fixing tea and a snack. Are they discussing religion? Most likely not. They’re talking about men, maybe even about the challenges of living with true believers. The men in the living room are fussing. The women are laughing. The real difference in this (terribly stereotyped) scenario, I respectfully submit, is not between the Muslim couple and the Christian couple, but between the men and the women.

Any time you try to talk about culture you are forced to generalize. If you constantly qualify your projections by acknowledging the wide spectrum of behavior in any one culture, you can’t reach any conclusions at all besides the fact that people are strange, which holds true everywhere. When it comes to human behavior, there are more exceptions than rules.

In general, though, there are two cultures in conflict in the world today. One is dominant, but unstable. The guardians of this culture tend to be “alpha males,” that is, men with a need to be on top of their worlds, who are aggressive, self-centered, ambitious, and willing to resort to violence. This culture has encouraged certain kinds of material progress but results in constant struggle and increasing divides between haves and have-nots.

The other culture is submissive but stable. This culture is maintained and propagated mostly by women. It is other-centered, conciliatory, patient, and prevents or tamps down violence wherever possible. This culture keeps the human world going, for without it, the dominant culture would tear everything apart.

I’m going to call the dominant culture male, though it includes many biological females. I’ll call the complementary culture female, though it includes many biological males. There is no question about which culture is uppermost today. Anywhere you find hierarchy, whether in a capitalist, nominally communist, or oligarchic society, the male culture rules. Wherever you find egalitarianism, cooperation, and collaboration, the female culture is in charge.

Not every society in history has been ruled by alpha males. Sophisticated justice systems; decisions by councils of elders; inclusive mores that provide for and protect society’s outliers; peaceful agrarian societies: all of these indicate the primary influences of women’s culture.

On the other hand, violence; the heedless destruction of human and other natural resources; the oppression of the lower classes: all these are sure signs that the male culture is running the show.

Clearly women’s culture evolved around the need to protect children from men’s aggression. If some sector of society did not propagate the values of caregiving, altruism, and sharing, that society would not survive two generations.

In a world of many languages, where communication was difficult, male culture evolved to settle disputes through physical violence. It would be up to the males whether a tribe’s territory expanded or contracted. The more territory, the more access to game, water, and fuel, the better the tribe’s chances of survival. If you see the world as belonging to “us” or “them”, you want the biggest, baddest guys on your side.

Our world today hangs in the balance in more ways than one. Scientists tell us that our behavior over the next decade or so will determine whether global climate change continues at a pace likely to doom our (and most other) species, or whether it will moderate to a manageable level. Nuclear proliferation proceeds at a rate where unstable regimes and non-state actors have access to weapons that could render the planet uninhabitable except by cockroaches and rats. Water pollution and over-use is at the point of making entire countries vulnerable to death by disease or famine.

Whether our species survives these crises depends upon another balance: the balance between male and female culture. Male culture has ruled, nearly planet-wide, for centuries, cementing its hold though tyrannies and then through the spread of capitalism, which values and rewards selfishness, aggression, and greed. But the destruction that attends these values is catching up with us. More and more people realize that we could very well do ourselves in if we continue on our current path.

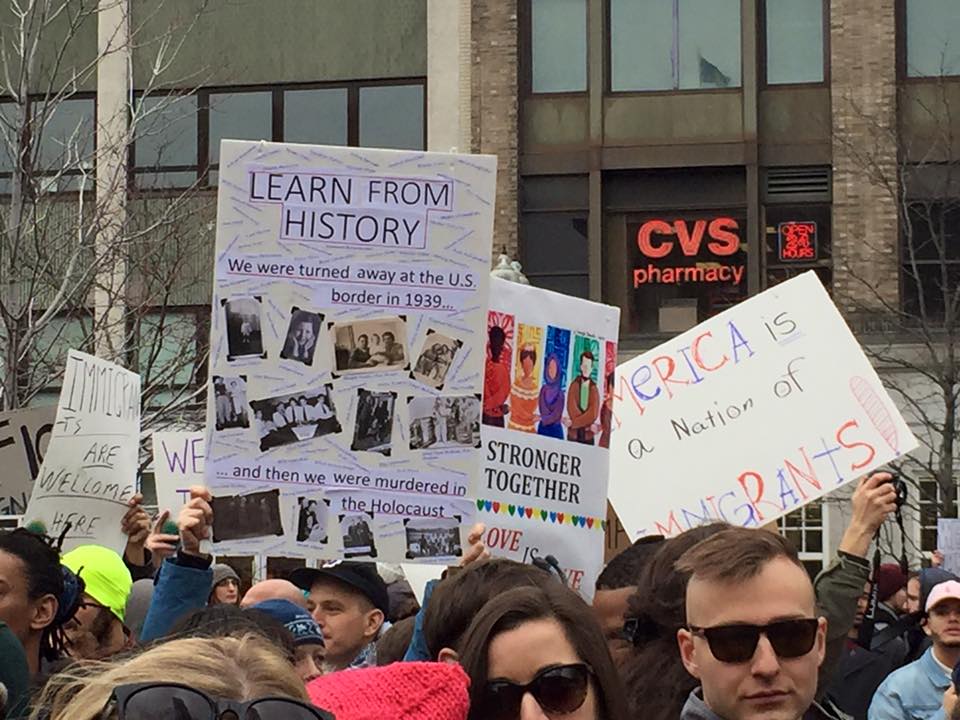

Meanwhile, female culture has begun to strengthen in ways unimaginable a century ago. Women’s liberation has barely begun, but its effects are threatening male dominance in every society. Some ancient techniques (violence against women and LGBTQ people, veiling, double standards on sexual experience) and some new ones (high heels, sexualization of younger and younger women, co-optation of women leaders) work against women’s rise, but the trend continues. Women have gotten the idea that they should participate fully in public life, and they are insisting on their right to do so. What has given this idea such strength and persistence?

I believe that deep in our collective unconscious, we know that women’s culture must assume dominance if humanity is to survive. We must stop hurting one another and start taking care of one another; we must stop wasting resources, and learn to conserve; we must clean up the messes we have made; we must stop rewarding greed, and place more value on sharing. Only women’s culture carries the tools and techniques to bring about these changes.

This necessary revolution, which seems so radical, would actually require only a shift in the balance of cultures. We just have to listen more closely to what Jung called the anima, the feminine side of our consciousness. The center in us that corresponds to female culture – the center of nurturing, caring, sustaining values and behaviors – must gain our respect, as it is the key to our species’ survival.

The movement toward women’s liberation arises from the deepest place in ourselves: the part that wants to live, and wants our children to live. Right now, many of the stories we tell ourselves are generated from our fear that survival is not possible. Even though every one of us contains the seeds of a new world, we despair of the possibility that they will grow and thrive.

When we choose our leaders, we should ask ourselves which culture they embody. We need more representatives of female culture to set public policy, whatever their gender. We need more women in positions of power, not because women are that different from men, but because they have been the custodians of the set of values around which our species must reform its behavior.

Those women laughing in the kitchen do not need to come into the living room and argue with the men. No: it’s the men who need to come into the kitchen, drink the tea, eat the cookies, and learn to laugh with the women.