Friday, May 10, is a cool, sunny day. Rising sophomores who lived in the Yard this year are carrying mattresses, couches, and huge cardboard boxes from their dorms. Parents have only 20 minutes to park in the Yard to receive them. The protest tents are not in the way, though so many gates are closed that there is some level of inconvenience for cars coming and going.

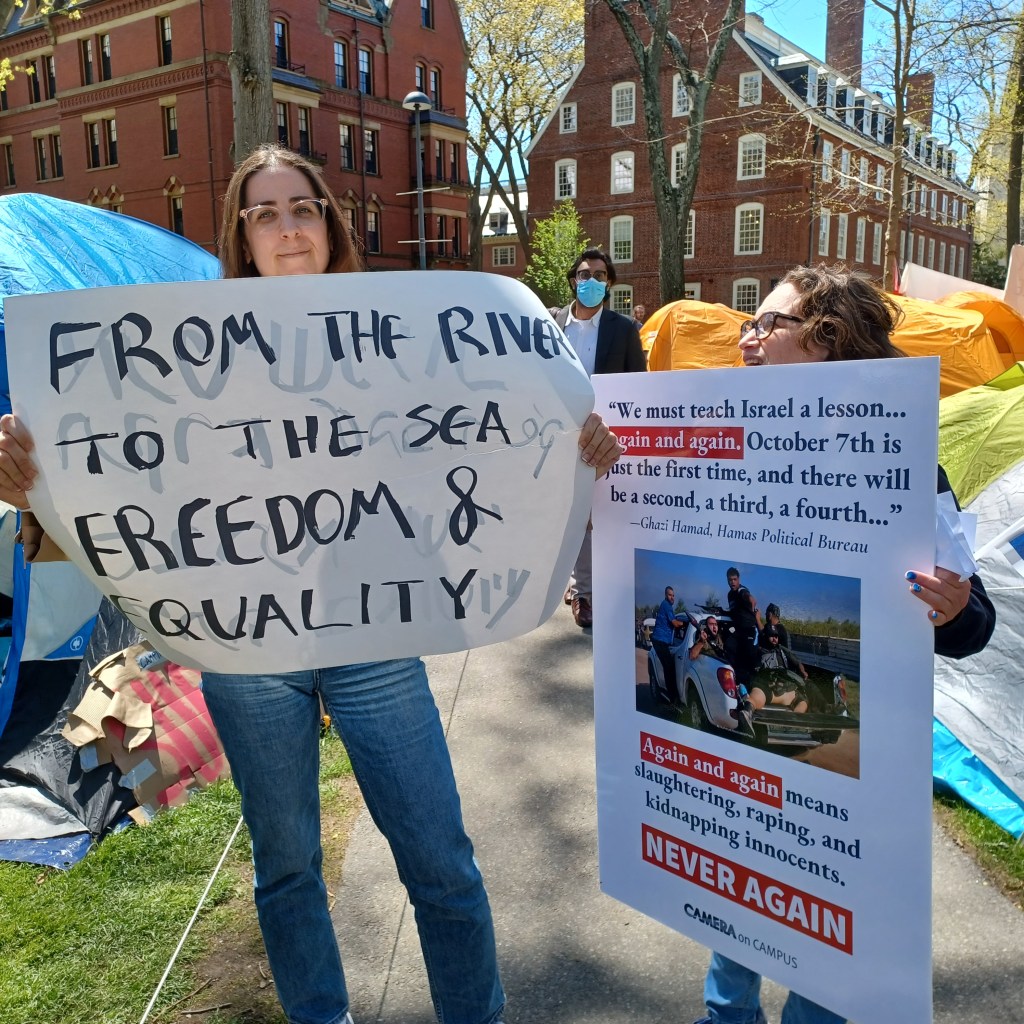

A few pro-Israel counter protesters play pop music on a radio very loudly, right next to the encampment, which is deep in discussion as usual. I don’t know why the music stops after a few minutes.

A protester asks friends on the steps of University Hall to help clean up the wet, dirty tarps on the “event space” next to the tents. Another remarks, laughing, “I haven’t had a shower in a week.”

People I knew from my campus labor union tell me that students who have been suspended or put on involuntary leave seem to have been chosen almost at random. They aren’t leaders or organizers, or even necessarily people who slept in the tents overnight. It’s more a matter of someone in the administration happening to see and recognize them, in spite of the masks or scarves many have been wearing.

Another press conference is scheduled for 2 pm. Most protesters go all the way around through the Science Center gates to get outside Johnston Gate where the press is gathering. I don’t want to walk that far, and I can’t hear the speakers anyway. Yard security and campus police are present, though not in great numbers; the tall bald guy who looks the most serious squats on his heels on a nearby path. The University’s president Garber comes out of Massachusetts Hall now and then, accompanied by a guard. I haven’t seen anyone else approach him.

Outside the gate, the crowd is chanting “Free free Palestine! Long live Palestine!” The Harvard protesters appear to have decided not to use the inflammatory chant of “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” or to call for an intifada, which means uprising or resistance.

I hear one woman, annoyed at not being allowed in, ask a guard about Askwith Hall, which is blocks away from the Yard at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She is not happy with his answer, and says to her companion, “Okay, let’s go to the media.”

My union friends and a rainbow-haired woman from the Business School think Harvard is treating this protest more harshly than previous encampments. They call it “the Palestine exception.” A student worker wonders if they lose ID access to buildings because of the disciplinary process, will that be grievable through the union.

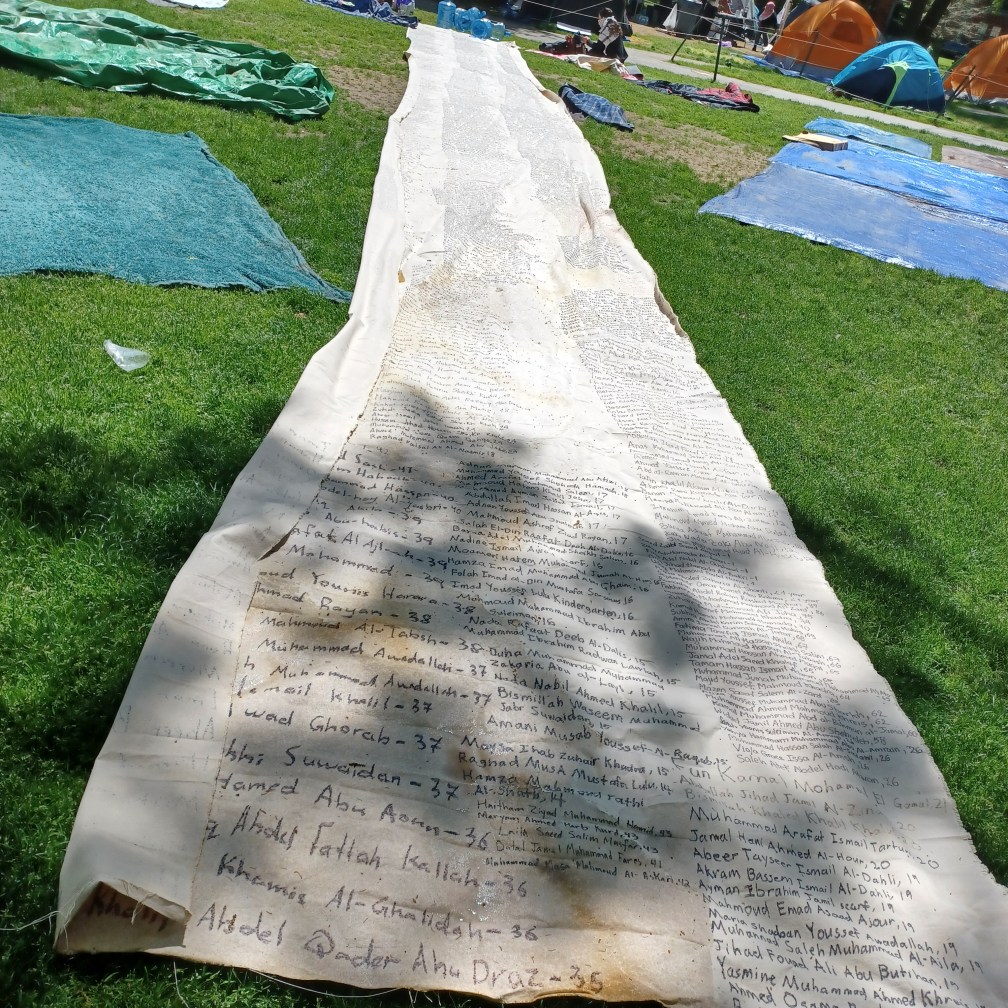

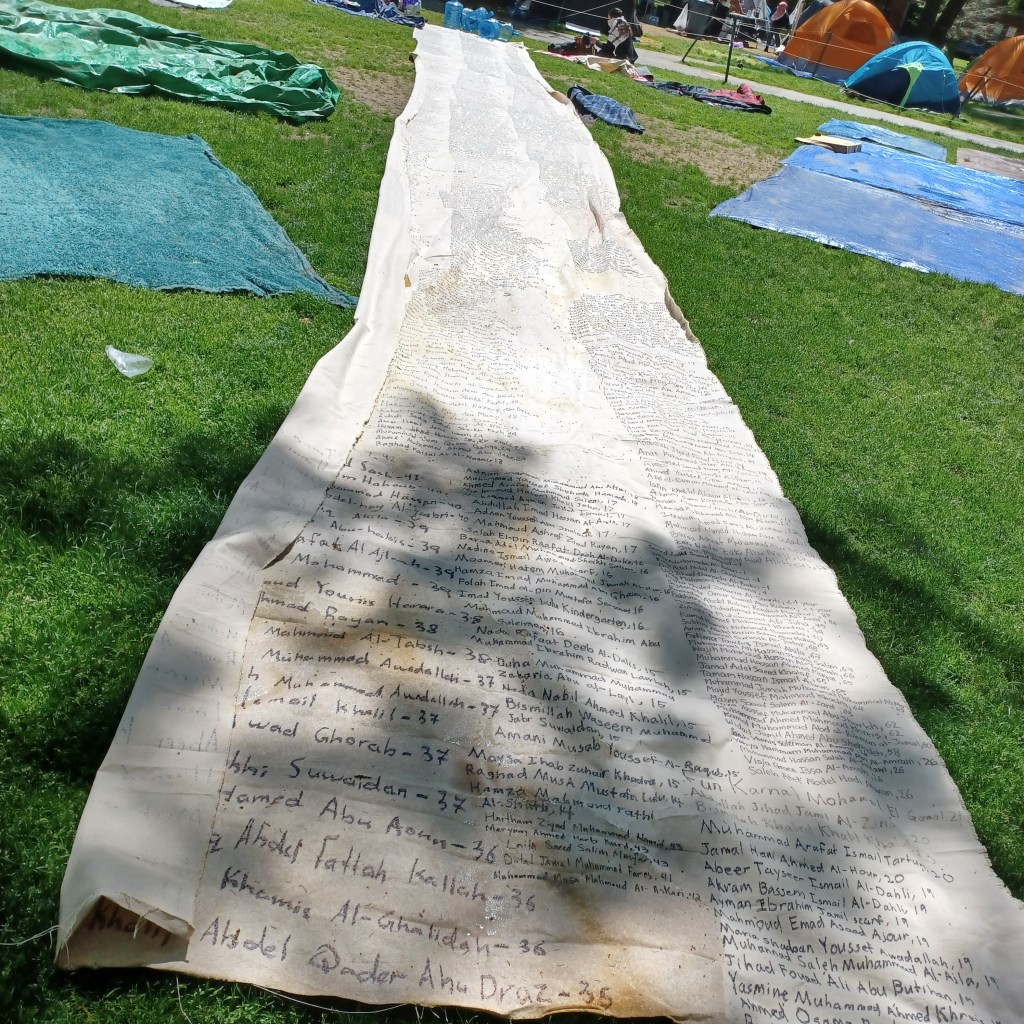

About 25 people attend a Muslim service in the “event space.” The young man leading the service often lapses into Arabic, but from what I can understand, he’s mostly talking about how we will return to the Creator after death. He talks about how many lives have been lost, and how many hospitals, homes, and schools turned to dust. He talks about “the dead earth” left behind, and “the will to destroy.” He says of the Israelis, “They built upon the imaginary [sic] that there was no one living in the land, that it was empty earth.”

The speaker says, “Somebody has taken the desires of their own heart as God,” taking for themselves the powers that should only belong to Allah. He notes that an Israeli real estate company is already trying to sell land for housing and luxury hotels in Gaza.

The most aggressive counter protester stands next to me. “Do you believe in this?” No, I say, I’m just listening. “You see they separate the women from the men.” So do orthodox Jews, I respond. “But this is 2024!” he says. Yes, I reply, and I don’t like it either, in any religion.

A helicopter hovers low overhead, evidently trying to disrupt the service. When the sermon ends and people bow and pray, I notice it sounds a lot like the davening during a Jewish service.

Supportive faculty and staff form a circle and hand out identifying pins, with the watermelon logo of these protests, and orange vests saying Faculty and Staff so they’re not taken for camp marshals. They expect the University to take the tents down soon, in the middle of the night.

A student who says he’s going to be “Ad Boarded” in a few minutes tells us about a supposedly secret meeting with President Garber. All the president did was tell the protesters how the endowment works. The student says 10 to 15 students were put on involuntary leave during the first raid this morning. Some never had their IDs checked at the protest, but most had been highly visible.

A student marshal in an orange vest speaks to a circle of others. “Don’t engage with police. Our job is to de-escalate.” She says some things I don’t understand. What is a stretchie, and how does it crack?

Later in the afternoon there’s a march and rally, attended by many more people than hang out in the camp. They go all around the Yard after surrounding Mass Hall for a while. I don’t go with them. I hate chants, and I’m tired.

A counter protester accuses one of the protesters of removing his sign from the foot of the John Harvard statue. “Not cool!” he says. A protester points out that the sign is still there; the wind blew it over. “You’re just not looking.” The wind has strengthened so that while workers try to lower the big American flag over the statue, it twists around the pole so they have to raise it, shake it, and try lowering it again several times before they get it down.

As I leave the Yard, I hear a brass band. Has somebody taken protest music to the next level? Then I spot a tuba over the head of a joyful line of people snaking down the Holyoke Street sidewalk, waving white kerchiefs. It’s not a protest. It’s a wedding. In the middle of all this difficulty and angst, life goes on.