Monday, July 26, 2004

Thirty-one police motorcycles are parked in front of the Boston Public Library, lined up in two neat rows. They seem to be there to protect the public from the Falun Gong people who are demonstrating their exercise and meditation techniques in Copley Square across the road. Falun Gong practitioners are persecuted in China, detained, tortured, and sometimes killed for their beliefs. But in Boston today they exude a cheerful eagerness to please.

Groups are practicing dance moves. There are a dozen or so fetching young ladies dressed in tight, blindingly pink bodysuits with flared legs and silvery ornaments; several dozen older women shaking their arms overhead, the bells on their bracelets tinkling up a storm; and hundreds of other men and women dressed in day-glow yellow hats, pants, and T shirts. The only thing I see to object to is their color scheme, which runs to the fluorescent. Maybe those motorcycles belong to the Fashion Police.

Black helicopters drone overhead. I don’t stick around for the Falun Gong show.

Near the Park Street mass transit station, Robert, a resident of Newton, Massachusetts, is walking around with signs bearing an unusual message: Give all living things the vote.

One of Robert’s signs, adorned with a googly-eyed cartoon slug, reads: “Universal suffrage means a vote for all. Elect-a-Slug! Will not nuke world; will not screw interns; did not invent internet; is not religious bigot. Do Not Vote Primate!”

Robert works for the Smithsonian Institute and used to contract for DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

“If ants had the vote, wouldn’t it be a better world?” he asks. I suggest that humans would have to form coalitions, perhaps with dogs and cats. “Those fellow travelers!” he replies.

Two nice ladies sit at a DNC information table near the T station, hatless in the hot sun. They’re pointing people in the wrong direction to St. Paul’s church.

![]() The ladies tell me it was “bedlam” here on Sunday with all the anti-war demonstrators. However they also say the protest was “very peaceful. Well controlled.” I’m not sure if they mean self-control or otherwise. Here come the black helicopters again.

The ladies tell me it was “bedlam” here on Sunday with all the anti-war demonstrators. However they also say the protest was “very peaceful. Well controlled.” I’m not sure if they mean self-control or otherwise. Here come the black helicopters again.

Half a dozen army MP’s, both men and women in camouflage that stands out in the urban jungle, relax in the shade of the T station, chatting and watching the tourists.

I talk to some of the men who live on the streets around here, among the few Bostonians who haven’t left town to escape the predicted madness of convention week. Frank has been homeless for 37 years. A car wreck left him disabled enough to be sent to a special school for kids, but not disabled enough to qualify for disability benefits. He is blue-eyed and curly-haired, and would be good-looking if he weren’t missing so many teeth.

Frank says it doesn’t matter who wins the election this fall. Whoever runs the country “does me no good. I’m still homeless.” His friend carries a grey blanket wrapped in plastic under his arm. What should the government do for homeless people? “Give us housing, that’s it!” he says. But Frank disagrees. He doesn’t want a hand-out, he wants an opportunity to work, and housing he can afford.

“If I get a job, they take away my check,” says Frank. “It’s a catch-22. No matter how I slice and dice it, I’m still fucked. There’s not a dime of difference. Democrats will give you lip service, Republicans will give you nothing.”

![]() Rena, from the state of Washington, is here with the Dennis Kucinich campaign. “This is the first time I’ve ever gone to investigate a major political candidate and found I like where he is on every issue. I’m astounded. Delighted. He gives me hope.”

Rena, from the state of Washington, is here with the Dennis Kucinich campaign. “This is the first time I’ve ever gone to investigate a major political candidate and found I like where he is on every issue. I’m astounded. Delighted. He gives me hope.”

Rena is helping guide people in to a social justice forum at St. Paul’s Church, where Kucinich and Jesse Jackson will be speaking later. She’s practicing what she calls “compassionate communication,” which seems to consist of saying necessary things gently, over and over. She has a sweet round midwestern face and curly red hair under her wide-brimmed straw hat.

Bunny, a thin woman in Birkenstocks with short white hair and glasses on a green-beaded chain, came down from Vermont. She’s in town to “bring progressive issues to John Kerry.” She hopes Kerry is keeping a lot of leftie ideas under his hat. But she promises, “If he gets in, we’ll be back in the streets the next day.”

An articulate young white man in a motorized chair and a DNC shirt is explaining Kerry’s money needs to two elegant young black women in office wear. They’re signing a petition. Meanwhile, delegates stroll up and down Tremont Street, unfolding maps and peering around for landmarks.

Some people in the small crowd on the sidewalk are wearing T-shirts that say “Regime Change Begins at Home”. One sign reads “Kerry and Bush are Against the Poor”.

Inside the packed church, I ask a man with a pleasant open face what his tag says — is he press or a delegate? “I’m nobody,” he says; “This is for the bus.”

Here’s Leslie from California again, the exuberant blonde I saw yesterday on the subway. Today she’s in a turquoise cotton top, white shorts and flipflops, smiling steadily, telling people entering the church, “Everywhere but the first two rows.” She was up at 6 a.m. today, she says, “doing the newspaper run.” Later, she plans to go take a nap. Tomorrow, she promises to be in full regalia again at the protest fair on the Commons. I wish I had taken a photo of her on the T in her little apron saying No More Bush, with its picture of a woman’s shaved crotch.

Four women are hugging one another near the entrance. “So glad you made it.” “I escaped!” “Let’s get our own pew.” One says, referring to the convention center I suppose, “Everyone who’s going in there is very well dressed. With huge IDs.” She moves her hands to indicate hang tags. They all laugh.

Sally, from Albuquerque, New Mexico, was at a Code Pink rally outside the protest pen when they tried to put up a banner. At the time, the father of a soldier killed in Iraq was addressing the rally. “Police were taking down this dangerous pink banner. There were a lot more police with machine guns than protesters. A little bit of overkill.”

Jim, a sturdy grey-haired man with glasses, a pug nose and a mustache, is wearing his Vets for Peace ball cap. He’s from Orange County, California. He says they set up crosses at Huntington Beach on Sunday at sundown, one for each soldier killed in Iraq. The crosses fill an acre of beach.

“Our best supporters are the young Marines” from nearby Camp Pendleton, says Jim. “We try to educate the public about the true cost of war, honor the fallen and the wounded, and think about the needs of vets once they return. Whether you’re for or against the war, we should honor the ones who are making the sacrifices. Older Republicans, Eisenhower Republicans, they see it. We’re not there to argue. We ask people to think about their government’s policies.”

Jim went across the United States with the National Vets Stop the War bus tour. “Thirteen crazy Vietnam vets, some from the first Gulf War, all suffering from various degrees of post traumatic stress syndrome! We had a good time though…The bus was decked out with graphics. People clapped and honked their horns, through the heart of America. The occasional person flips you off, but not much of that.”

The vets came to Boston last Tuesday for a national conference at Emerson College. Daniel Ellsberg and Ralph Nader were there too. “I was afraid Ellsberg was going to jump him!” says Jim, “But he said he’d wait til later.”

“We’re patriots for peace. We believe in America strongly.” Sally, who’s been listening, says: “We don’t think it’s patriotic to support a criminal war.”

Onstage, a young Asian-American woman talks about being made to feel like an outsider after September 11. She says of her community, “Everyone has had something happen to them or to someone they know.”

I watch Kucinich speak for a while. He’s so short. I’m short too, but I’m not about to run for president. If liberals could just stack him up on top of Robert Reich and Michael Dukakis, they’d have the perfect candidate: really smart, and really tall. My favorite Kucinich line: “It doesn’t matter where you come from, but where you’re going, and who you’re bringing with you.”

Jesse Jackson delivers a rousing speech on building a movement “from the bottom up, not the top down,” but the church is hot, and I sneak back out to the sidewalk. An older woman holds a banner that reads “Invest in caring, not killing”. About a dozen young people trudge in a circle in front of the church, chanting “Bush, Kerry, no solution, fight for a Communist revolution”. The other people milling around are ignoring them.

A couple of libertarians carry signs reading “Conservatives Organized to Crush Kerry/ End the Nanny State/ Free the market and the rest will follow/ Liberty: It’s what’s for dinner” and “Enjoy Capitalism!” The tall green-haired one also carries a large Don’t Tread on Me flag.

Other sign slogans: “War is Peace. Freedom is Slavery. Bush is President.” “SHARING will save the world.” “Another World is Happenin’.” One popular T-shirt has a picture of a backbone with the various vertebrae labeled: instant runoff voting; end weapons trade; reject water privatization; embrace diversity” etc..

LaRouche supporters, mostly black, mostly male, sing several choruses of an ode to their leader, whom they call an FDR Democrat. Very nice harmonies. A guy in a red polyester Hawaiian shirt holds a sign saying “Democrats: Hermaphrodites are People Too!” I’m pretty sure it’s a guy.

On my way to the FleetCenter, which I would much prefer to call the New Garden, I ![]() overhear three policemen talking about possible protests. I can just catch a few scattered words: “…blood…excrement…rumor…” A few minutes later I visit the result of that kind of rumor: the protest pen across from the FleetCenter, formally named the Free Speech Zone. A chilling concept.

overhear three policemen talking about possible protests. I can just catch a few scattered words: “…blood…excrement…rumor…” A few minutes later I visit the result of that kind of rumor: the protest pen across from the FleetCenter, formally named the Free Speech Zone. A chilling concept.

And it’s a chilling place. Long, dark, narrow, dirt-floored, roofed by the iron hulk of an obsolete overpass, with razor wire on top and heavily armed guards on the look-out. The area is surrounded by concrete Jersey barriers and two high rows of chain link fence, plus a bunch of plastic sheeting. Netting is strung between the fence and the overpass. The space suggests an attempt to create Tupperware for terrorists.

A small grey-haired man stands off by himself, holding a poster that reads: “Design by Sharon Rumsfeld Associates.”

The podium is located toward the rear of the space, behind a structure that might be a mechanical shed, close to the fence. One woman remarks to me, “It’s like if you put a couch in your living room turned around toward the wall.”

The space is mostly deserted, now and also on other days when I drop by. There are a dozen or so Republican activists wearing giant cutout flipflops with holes for their heads, and about a hundred anti-abortionists. A man with a naked buttocks mask on his bottom and devil horns points out Randall Terry, one of the movement’s leaders, a telegenic guy in a handsome tan suit.

The anti-abortion people have covered nearby sidewalks with slogans in chalk, which have begun to be erased by passing feet. Two burly men are holding up big signs: “Support President Bush/Trust Jesus.” A friendly-looking old man in an Uncle Sam costume also holds pro-Bush signs. “I’m so tired,” he says. “Not of getting my picture taken, I was up late…”After I take his photo and thank him, and say I hope he’ll get some rest, he says “I hope you lose.”

The anti-abortion crowd makes way for the next group of protesters, who turn out to be vicious homophobes. They carry signs like “Boston = Sodom” and their speakers say such venomous things that I can’t bear to stay and listen. One man stands stolidly before the platform holding up both middle fingers. He’ll probably be okay. There are certainly enough police around to keep him from getting stomped to death.

When I come back later, a group arguing for the rights of Palestinians has taken the stage. One young Jewish woman says, “I feel a connection to the land of my ancestors. I just don’t feel the need to own it.” Signs on the fence read: “Is this what democracy looks like?” “Palestine always looks like this.” And “Whatever happened to the First Amendment?”

I talk with Kate, from Cambridge, and Priscilla, from Andover, Massachusetts, who are watching the action outside the pen. Priscilla says she believes in free speech, “but the way these anti-gay people are talking, so ugly, sick and hateful…”

Bumpersticker spotted on a barricade: “I need to find a florist who can send two bushes to Iraq”.

At the FleetCenter, long lines of people are going through the security checkpoints inside big white tents. They’re confiscating everyone’s water bottles. Are we feeling safe yet? I’m actually grateful to the guard who dumps out the contents of my backpack, because my feta cheese wrap has leaked through its paper sack and was about to ruin my notebook. He didn’t notice my little bag of nuts and dried fruit, or else didn’t consider them a security risk.

At the entrance to the building, pigeons walk among the crowd. Overheard from a group of radio press: “Looks like birds are going to be a problem.”

Rabiul, a Deaniac from Kansas, is waiting for a friend so he takes a minute to talk with me. He’s a businessman who was born in Bangladesh and has lived in the U.S. for 20 years. His main concern in this election, he says, is “Openness. We have a right to know what our government is doing.” He also worries about maintaining a healthy environment for future generations.

I ask Rabiul if he had any problems with people after September 11. Even friends “gave me a different look,” he says. His son was outside playing, and some neighborhood children teased him, saying “You’re from another country, go back to your country.” His son replied, “I was born here.” Rabiul told him he was right to say that, and not fight. “By force you cannot get respect.” He adds that right after September 11, one of his neighbors told him to let him know if anyone gave them trouble.

Rabiul says he went back to Bangladesh for a visit in 1999 and had only good things to say about this country. He tells me that when he brought his elderly parents to America, they couldn’t get insurance and couldn’t apply for citizenship because they were too old to learn English. He was desperate to get them health care, afraid they’d come all that way just to die.

Rabiul went for help to Kathleen Sebelius, the Kansas insurance commissioner at that time, now governor of the state. She went to work on the problem, and three months later had a new regulation in place so his parents were able to get health insurance.

I enter the FleetCenter at the same time as Michael Moore and Al Franken, who greet each other over the heads of the swarms of press. I make my way to the fourth level print media area. An officious woman named Mary says I can’t sit there while wearing my hat. I’ve wrapped an orange plastic banner around it that reads “First Amendment Zone,” which the press area is evidently not. Mary is worried about how the area looks on television. Another writer has a classy little black straw hat on that must meet the dress code. It’s boring here anyhow and I go wandering again.

An announcer asks the crowd to pose for the official convention photograph. “Please look at the digital clock across from the stage, toward the Fox 25 News banner,” she says. At the mention of Fox, the crowd boos lustily. And then grins for the camera.

Music so far: “We are Family” and “Dancing in the Street”.

There’s a very large man with a ponytail dressed head to foot in bright orange out in front of the crowd, dancing. Fortunately he’s a pretty good dancer because you feel compelled to look at him, regardless.

Now I’m in what people are calling the nose-bleed seats, rising steeply in the top tier just under the bags of a million balloons. Right now they’re not too crowded. I sit next to Donald, whose wife Kaye, a schoolteacher, is one of the Texas delegates. We’re both glad to have a railing to hold onto.

Don’s a retired sheriff. He plans to run for Justice of the Peace. It annoys Don that Bush claims to be a Texan, pointing out he wasn’t born in that state. “He broke Texas, and now he’s breaking America,” Don says.

The musicians are playing a version of “Rollin’ on the River” reworded into “Kerry in the Future” as far as I can tell. The Dems need to lose this little ditty as soon as possible.

Gore is saying “America is a country where any boy or girl can grow up to win the popular vote,” and gets a big laugh.

Now Hillary’s speaking, but I’m listening to Don. He was a police investigator enforcing environmental laws for a while. “We cleaned up the water so you can swim in it again,” he says proudly. He once got to guard Barbara Jordan, the late black congresswoman from Texas, who, Don thinks, was “a great lady.” Hillary is standing on stage with the other congresswomen, and the band is playing “Everyday People.”

Joyce, sitting nearby and listening to our conversation, identifies herself as a banker from Kentucky. When I tell her my kids were born in Kentucky, she gives me her state pin. Not to be outdone, Don gives me his little American flag pin.

It’s hot up here and I’m tired, but I stick around to hear Jimmy Carter, in my opinion the only real Christian we’ve had as president. Straight and slim at 80, he’s not speaking as clearly as he used to, but the crowd responds to him with great affection.

I leave before Bill Clinton speaks. I’m sure he’ll drive people wild. We’d re-elect him in a heartbeat if we could, no matter what the meaning of “is” is.

Tuesday, July 27, 2004

On the subway, I meet Debrosha and her daughter Katie, the Massachusetts coordinator for Rock the Vote. They’re lugging materials for events around town. Rock the Vote is strictly nonpartisan. They don’t care who you vote for as long as you vote. Clearly, though, registering young people and black people will help the Democrats.

Katie’s going to school at Tufts. Her mom came in from Allentown Pennsylvania to help her this week. Debrosha is a big woman with a wonderful smile, which shines forth whenever she looks at her smart, pretty daughter. She’s exhausted already though, doing so much walking in this heat.

Katie says, “The last election showed us how much one person’s vote counts.” She tells me that when young people say they’re non-political, she asks if they know there’s a bill to reinstate the draft. “That’s a reason to vote right there!…I don’t think you have a right to complain if you don’t do anything about it.”

She’s wearing a black stretch band across her chest that reads “fcuk you, i’m voting” — from French Connection, United Kingdom, hence the fcuk acronym. “It’s a little harsh, but people my age, this is the kind of thing that gets them to look.” Katie tells people to find out what the candidates stand for, not to vote a certain way because their parents or their friends do.

Katie doesn’t feel like the media are doing a good job letting people know about the candidates’ voting records and backgrounds. “We spent a lot of time on the Clinton controversy, and I think if we were willing to do that, we should be willing to educate people [about the candidates].” Not surprisingly, education is one of her main concerns. “Other countries are catching up to us because they’re willing to educate their people.”

![]() Debrosha says they’re sending Katie’s 12-year-old brother to a private school on scholarship; they have no money. “I’m really a public school person, but I can’t sacrifice my son.” The last straw was her son’s public school French class, where they had no textbooks. The teacher was good at Spanish but didn’t really speak French well enough to be teaching it. She wrote the lessons on the blackboard for the kids to copy, and if they copied the lesson wrong, they learned it wrong.

Debrosha says they’re sending Katie’s 12-year-old brother to a private school on scholarship; they have no money. “I’m really a public school person, but I can’t sacrifice my son.” The last straw was her son’s public school French class, where they had no textbooks. The teacher was good at Spanish but didn’t really speak French well enough to be teaching it. She wrote the lessons on the blackboard for the kids to copy, and if they copied the lesson wrong, they learned it wrong.

Debrosha’s first vote was for Carter, and she’s still proud of him. “He always tried to help the little people.”

We part near the Commons, where the Falun Gong people have set up horrifying tableaux showing various torments they’ve been subjected to in China. Torturers and torturees pose with the same disciplined stillness as the meditators sitting on the grass, minus the blissful little smiles.

On the street later on, checking the line outside yet another social justice forum, I meet Fernando, a radio reporter from LA. I tell him I’m starting to pick up some Spanish from a late-night Latin music program called Con Salsa, and he says, “Never forget, there are 500 million people waiting to be your friends.”

Boston has hung lush baskets of flowers from lampposts all around downtown. There are red, white and blue clothes and furniture in store windows, and an “Art is Democratic” banner over an art gallery. The streets are unusually empty.

I wonder if anyone warned the out-of-town young ladies in their high-heeled backless sandals about Boston’s cobblestone sidewalks.

The hemp store is flying an American flag out front with a sign pointing out that this flag, like the original, is made of hemp: “If true patriots like Washington and Jefferson grew hemp, why can’t we?”

![]() At Copley Square, the American Friends Service Committee has set out a pair of combat boots for every American soldier killed so far in Iraq, and a big pile of street shoes, though not big enough to represent every Iraqi civilian casualty.

At Copley Square, the American Friends Service Committee has set out a pair of combat boots for every American soldier killed so far in Iraq, and a big pile of street shoes, though not big enough to represent every Iraqi civilian casualty.

Grigory, a Russian from New York City, stands near his sculpture commemorating all the victims of terrorism worldwide. It includes two clear plastic towers like Boston’s holocaust memorials, covered with photos of the firemen and police who lost their lives at the twin towers, toy buses and trains that have been crushed and speckled with red paint, a world map with the locations of atrocities marked in black, a tiny picture of Daniel Pearl, and the photo of a little girl with the words, “People Protect Me.”

Grigory says, “I ask – for me is question – what to do with this?” I take his picture. He seems wistful; a man with many questions and no answers.

Dawn and Andy, independent media people from Rochester, New York, are grabbing people for interviews about their reactions to these displays. Andy says, “I’m outside the two-party system, voted for Nader last time. If I’d lived in a swing state I would’ve done different.”

Near one of the delegates’ hotels, I meet Peggy, on the finance staff for the DNC. This is her fourth convention. “LA was a lot bigger.” She’s a Carter fan too: “He’s everybody’s hero.” She finds the convention is useful “for the delegates to compare notes and network, get close to the politicians. It energizes you, kind of makes you feel like what you’re doing at home makes a difference. Makes you more committed, reinforces you in the fight.” She’s in a hurry and hustles off to work.

Flashing my press pass, I get a seat on a delegate bus. I ask my seatmate, Gil, a delegate from Berkeley, California, if he’s been to any parties. “Six people in a closet: call it a party, it’s a good time!” His main beef is Bush’s foreign policy. “This last year, we’ve been a bully, or people think we are. We should use our influence, not through strength but through wisdom.”

Gil is an Asian-American with two children. He misses the eight years of peace and prosperity under Clinton. He’s concerned with working family, labor and education issues. As a fire captain and paramedic, “I see the trends. We go on more calls because people aren’t getting health care. The way speakers presented last night was right on. We need health care for everyone. And strengthen first responders to reduce crime.”

He adds, “I have discussions all the time with my Republican friends. We’re not bullies. We’ve never gone into a country and taken over like this…We’ve lost long-established relationships with just about everybody. Our administration does not collaborate with groups internally or externally.” He’s excited to be at the convention “to get our message out: we’re going to forge change that will benefit our country.”

The bus takes a peculiar, twisting route through the underground arteries that are closed to other traffic for the week. When we get to the FleetCenter, we can hear an amplified voice from the protest pen. It’s loud but distorted. I hear something about how the Bible says homosexuality is a sin.

Signs facing the bus parking area from the pen: “Don’t Cage Liberty: Cage the Fear-Mongers.” “Did the Patriots Die for This?” “Pens are for Animals!”

Also: “Kerry: Respect the World Court – Israel’s Wall is Illegal!” “Occupation is Oppression.” And “FUTURE OF THE FIRST AMENDMENT.”

Just outside the FleetCenter, I speak with Vincent, a square-faced, white-haired man in a union T-shirt, the Kerry co-chair from Fresno, California. Vincent is upset. He shows me a small paper sign with a photo of a woman’s eyes within a Muslim headdress and the slogan: Say No to War in Iraq. He had five of these, but security took away the other four. Why are the Democrats stifling dissent, he wants to know.

“Unity, fine,” says Vincent. “But to enforce it like this is not democratic.” He’s trying to get other delegates to make signs and hold them up later, but so far has not found anyone to go along with him. One of the political directors told him they don’t want to “send a bad message.” Stopping war is a bad message?

I spend a little while trying to find out who makes the rules about what to confiscate. I ask a policeman, who points me to a secret service guy, who says it was up to the DNC people. Then I ask a small young woman with a DNC volunteer T-shirt, but she has no idea. This is her first question on the job and she is clearly crestfallen at being unable to answer it.

Inside the Center, the band is playing “Celebrate Good Times.” Three black women in the Oregon delegation are dancing together. I’ve followed Vincent in his quest for fellow dissenters. Joe, a doctor from New Hampshire, says “I’m proud of you for speaking out this way,” but refuses to join Vincent’s protest. Joe says there’s a close race in his state and he doesn’t want to embarrass former governor Jeanne Shaheen.

Vincent says, “If you can’t speak out at a convention, where can you speak out?”

I notice the Kansas delegates hold up home-made signs when Governor Sebelius, Rabiul’s hero, begins her speech, so I go over to ask how they got them through security. The state whip says they gave the signs to the DNC person assigned to their delegation, who said any sign was okay as long as it had a cardboard tube handle and not a stick. But I can’t find Vincent again to tell him. His signs had no stick, anyhow.

![]() Anthony, an official-looking person whose position I fail to discover, says: “You need some standards. No obscenity. You don’t want signs on national TV that might be offensive, but if it’s a message of peace, I have no objection.”

Anthony, an official-looking person whose position I fail to discover, says: “You need some standards. No obscenity. You don’t want signs on national TV that might be offensive, but if it’s a message of peace, I have no objection.”

Joe, the whip for Massachusetts, says: “There are probably twenty valuable minutes here, prime time. You try to choreograph. Last night I saw a half a dozen rogue signs.” He adds, ruefully, “We’re living in a different world.”

I ask Joe about the protest pen. “The Dems didn’t set that up, a judge did that,” he says, which is not the case. He points out the pink scarves people are wearing that say “Give Bush a Pink Slip” to show that all forms of free expression are not being repressed.

Tonight in the writing press area, before Mary kicks me out again because of the hat, I meet Wayne, a very nice guy who is distributing hard copies of the podium speeches. He tells me about the media information room on the third level where he gets the handouts.

This place becomes my favorite part of the building. Only a few kinds of pass will get you onto the floor, which has its own escalator. Another round of security keeps everyone but some media people out of the corridor that leads to the media info room, CNN’s space, storerooms full of folding chairs and bottled water, and one of the entrances that lead to the stage.

It’s in this well-guarded hall that I get within six feet of Hillary, looking fabulous in a light blue suit, and brush against Senate minority leader Tom Daschle as he hurries off the floor. I also see several other famous people, but I don’t know who they are.

By 8 o’clock, I’m not feeling up to making any more new friends, so I head out. But en route, I encounter the young volunteer who couldn’t answer my question earlier. She’s radiant with pleasure: someone gave her a pass so she could get inside. “You’re leaving? But this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity!” Meekly, I turn around and sit through several more speeches before giving up.

I leave through a break in the fencing where security of several stripes makes sure people can get out but not get in. Just outside, a woman in a pink robe cries, “Hey! I made that banner!” She is looking at my hat.

![]() So I meet Robyn Su, who created the plastic First Amendment Zone banners three years ago, when “we discovered they were keeping protesters away from Bush and the media.” Her serene pink presence signifies a level of alert that has nothing to do with Rumsfeld’s screwed-up rainbow. He was so unfamiliar with the concept that the alert colors go red-orange-yellow-blue-green, instead of green-blue. But we never seem to reach those peaceful frequencies anyway.

So I meet Robyn Su, who created the plastic First Amendment Zone banners three years ago, when “we discovered they were keeping protesters away from Bush and the media.” Her serene pink presence signifies a level of alert that has nothing to do with Rumsfeld’s screwed-up rainbow. He was so unfamiliar with the concept that the alert colors go red-orange-yellow-blue-green, instead of green-blue. But we never seem to reach those peaceful frequencies anyway.

My night isn’t over yet. On the train home, Barry and Linda are still fizzing with excitement. “We’re not press, we’re troublemakers.” He’s been telling people that Bush had sex with Don King. “There are pictures!” I personally would be thankful if Photoshop had not made that particular image possible. Barry is from New York, where he has been happily making trouble for three-odd decades.

Linda is just along for the ride.

Wednesday night, July 28, 2004

I hitch a ride on the hotel bus after work. Mary, a plump, attractive blonde, is an alternate delegate from Alameda, California. She’s felt “pretty disenfranchised” since the last election. “I’m raising a girl, and it feels increasingly unsafe. I looked at the candidates way early. I read a lot, and thought that Kerry is aligned with what I think we need to be doing. And happily, other candidates had a lot of good things to say. But I don’t know if they were the ones to take the fight all the way. It took a wide range of viewpoints in the campaign to make us realize we could all come together.”

Because of their little girl, Mary says, “education is a huge issue. We [California] went from being one of the best to the worst.” She tells me that tuition at state colleges has gone up 40%. “My sister isn’t making enough to pay for the last semester she needs for her teaching credentials. She has to pay someone to watch her teach, and she’s been teaching for four years – in east LA. She went to find out about programs to help teachers in high-risk areas, and she was told they weren’t funded. They’re just words on paper.”

Mary’s husband, Phil, is an attorney. “We’ve generally ignored the authority of the international community,” Phil says. “It’s as though you were arrested and taken to court, and you walked out, saying this court has no authority over me.” Phil and Mary are amused at all the media attention they’re getting at a convention where media workers outnumber delegates almost 3 to 1. “These television people wanted get footage of us packing to leave. Well, sorry, we’re already packed!”

Phil and Mary get into a conversation with a sports lawyer, another alternate, which lasts until we get to the FleetCenter. They’re all concerned about electronic voting.

![]() Nobody bothers me in the fourth level writing area tonight, since it’s raining and I left my hat at home. Supposedly security isn’t allowing umbrellas into the arena. The local convenience stores have run out of ponchos.

Nobody bothers me in the fourth level writing area tonight, since it’s raining and I left my hat at home. Supposedly security isn’t allowing umbrellas into the arena. The local convenience stores have run out of ponchos.

Somebody here has been bothering another writer though: Marsha, a crew-cut woman in a wheelchair who has a wheelchair symbol tattooed on her shoulder. She writes for Mouth Magazine, “The Voice of the Dislabeled Nation.” I hear a fuss, and see her fuming; steam is almost visible, rising from her ears. A tall, broad-shouldered, well-dressed man with stylish grey hair has just stalked away. “He said, That’s my seat, get out of my seat,” Marsha says. He wouldn’t identify himself when she asked him, or when I asked him either. “I’ve never known anyone to be so rude!” she says.

Marsha tells me she used to work for Newsweek before she became disabled with multiple sclerosis. “They say it’s the most accessible convention in history, and it’s a nightmare.” There was a piece of rubber a couple of inches high that she couldn’t get over at the entrance, for example; “Someone had to lift my wheelchair over it.” At the disability caucus, blind people asked for the braille versions of the handouts but the DNC didn’t have any.

The band is playing “Power to the People”. Dennis Kucinich is getting up to speak.

![]() The mysterious grey-haired man says that Marsha assaulted him “verbally and physically.” He says the seat belongs to a writer “for UPS” who’s in a wheelchair. I said, if he comes, I’m sure she’ll move. He says if she won’t move, he’ll call security and have her arrested. I get distracted for a few minutes, and when I look again, Marsha is gone. In her place is a young man in a ball cap, without a wheelchair. I’m betting he’s not with UPS, either.

The mysterious grey-haired man says that Marsha assaulted him “verbally and physically.” He says the seat belongs to a writer “for UPS” who’s in a wheelchair. I said, if he comes, I’m sure she’ll move. He says if she won’t move, he’ll call security and have her arrested. I get distracted for a few minutes, and when I look again, Marsha is gone. In her place is a young man in a ball cap, without a wheelchair. I’m betting he’s not with UPS, either.

Jarrett the second and his father, Jarrett the first, are waiting in this area for Al Sharpton’s turn to speak. Jarrett the younger has been called the Reverend’s “Mini-Me”, and his hair tells you why.

Jarrett junior is the National Youth Director for Sharpton’s civil rights organization, the National Action Network. Jarrett got involved with Sharpton when he came to Phoenix, Arizona, where he and his father live. “What impressed him most: I registered ten thousand people to vote, through the grassroots level, at churches in the African and Hispanic American communities. We broke the back of the Republican stronghold.” Jarrett junior is seventeen.

“Poor education is hurting us everywhere,” he says. “No textbooks in schools. Lack of qualified administrators and instructors. Lack of security. Lack of civic pride in our communities. These all lead to our downfall. The state of education is leading to a generational trend of disenfranchisement among African-Americans, poor whites, and other minorities.”

Jarrett senior keeps stopping himself from interjecting his comments into our conversation, determined to give his son the lion’s share of limelight, if that’s what I’m providing here. He’s a disabled vet who “helped the Reverend shape his agenda on veterans’ issues.”

Sharpton’s speech electrifies the speech-weary crowd – even some people in the press area are whooping and hollering by the end of it. The Jarretts go downstairs to rejoin his entourage.

![]() The programmable strip of neon that runs all around the top section of the arena usually shows either white stars racing on a blue background, or one of the catch-phrases like “A Stronger America”. During Sharpton’s address, it reads “SHOUT! SHOUT! SHOUT!”

The programmable strip of neon that runs all around the top section of the arena usually shows either white stars racing on a blue background, or one of the catch-phrases like “A Stronger America”. During Sharpton’s address, it reads “SHOUT! SHOUT! SHOUT!”

I head up to the seventh level, where tonight all the seats are full. I hear someone say that the DNC gave out three times as many passes as there are seats. Some of the overflow crowd sits on the floor out in the hall, watching the whole thing on television. I sit down next to Zachary, who goes to Tufts University in the Boston area, and Bob, from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Zachary is studying international relations. “It’s no surprise that the rest of the world wants Kerry to win,” he says. “They don’t think well of us right now.”

“I’d like to see some improvements in homeland security,” he adds. “Our seaports are largely unprotected from weapons of mass destruction, bio-weapons and nukes coming in. Bush likes to say he’s tough on terrorism, but we’re almost as unprotected as we were before 9-11.”

Bob has been around long enough to know that some things are easier said than done. “The key is if we can increase security at ports without endangering freedom. The fact that we have screeners at airports, it’s not making us any safer. What’s making our aircraft safer is, now [if there’s a highjacking attempt], passengers know that if they don’t do something, they’ll die and take thousands of people with them, so now they’ll act. Before, they thought if you would sit down and be quiet, nothing will happen.”

Bob says he’ll give me a quote “you’re not going to print.” Okay, I say. “George Bush is a revolutionary,” he says. “He’s trying to change the nature of America and reverse the direction we’ve been traveling in for the last 70 years. He tolerates no dissent, no disagreement. In a different culture, he could easily be an Ayatollah Khomeini.”

I think of Bob a few days later when I see a bus with a big poster for Louis, Boston, on its side that reads: “Free speech is a luxury.” Does that mean most people can’t afford it?

Bob goes on to say, “When someone knows that God is on his side, and anyone who disagrees with him is against God’s purpose, he’s capable of anything. Whether in fact George Bush would do ‘anything’, I don’t know. But we have indications — Iraq, for example – that it’s possible.”

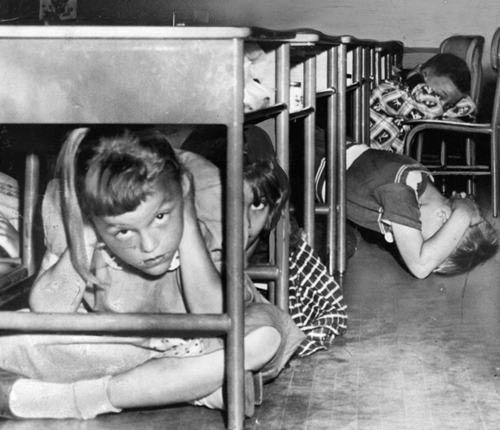

![]() Zachary adds, “What’s scary is what happens if there’s another terrorist attack in America. What if there’s a nuclear attack and three million die instead of three thousand, what would we do?”

Zachary adds, “What’s scary is what happens if there’s another terrorist attack in America. What if there’s a nuclear attack and three million die instead of three thousand, what would we do?”

It’s starting to feel like a small town in here. I see two girls from western Massachusetts, wearing Muslim headscarves, who were so anxious to get inside they couldn’t spare a moment to talk with me when I saw them earlier. This time I’m already in conversation with Zachary and Bob, so I just wave to them and they wave back to me, smiling.

I drift back to the press-only third level and practically smash into Jesse Jackson, who’s in a big hurry. I tell his retreating back, “Loved Green Eggs and Ham!” He gave his reading the full fiery Baptist preacher treatment on Saturday Night Live a few years ago, one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen. Come to think of it, though, that’s probably not what he wants people to remember him for. Jesse! Love your policy speeches, babe!

Security has closed all the entrances to the convention floor by now. Most of the escalators have been reversed, so you can leave but not come back. Trying to find your way around is like being trapped in an Escher print.

![]() All right, I’m leaving. I’m going to put in some hours on my day job again tomorrow so I don’t use up all my vacation time on this spectacle. First, though, I try to have a convention party experience. I go to a bar near the FleetCenter to check out the Rock the Vote party, but Katie isn’t there, and Coyote Ugly doesn’t have nearly as many customers as it has bras flying from the rafters, and the band is much, much too loud.

All right, I’m leaving. I’m going to put in some hours on my day job again tomorrow so I don’t use up all my vacation time on this spectacle. First, though, I try to have a convention party experience. I go to a bar near the FleetCenter to check out the Rock the Vote party, but Katie isn’t there, and Coyote Ugly doesn’t have nearly as many customers as it has bras flying from the rafters, and the band is much, much too loud.

I’ve heard the Red Hot Chili Peppers are playing a big party on Newbury Street and press can get in, so I give it a go. You can hear the band from blocks away and they sound terrific. But when I finally snake my way through the crowds in the street to the front entrance, a security guy tells me I could have come between 4 and 6 to get a special ticket, but it’s too late now.

Back on the subway. Here I meet James, an events coordinator for groups like Planned Parenthood, which has volunteers handing out stickers in the arena and sometimes just plastering them on unwary passersby. His main issues are reproductive choice at home, and the global “gag rule” the Bush administration has imposed on family planning groups abroad. If they even mention the option of abortion, they can’t get any federal funding. For these interests, “Thank my mother,” James says, a teacher who dragged him to union events while he was growing up in Colorado. I take a photo of him next to a guy with a delegate’s pass who can’t get a word in edgewise.

Katie, Laura and Joe are heading back to Tufts, where they’re staying in a dormitory. They took a 24 hour bus ride from Kentucky to get here, hoping to get into the convention somehow, as they came without any passes.

![]() Laura’s from Illinois, a sophomore at Bowling Green, Kentucky, who doesn’t know what she’ll major in yet. She has a migraine. You can’t tell it from her smile.

Laura’s from Illinois, a sophomore at Bowling Green, Kentucky, who doesn’t know what she’ll major in yet. She has a migraine. You can’t tell it from her smile.

Katie studied journalism and political science at the University of Kentucky, with a minor in women’s studies, and is now doing graduate work in urban policy at the New School in New York.

Joe’s a political science and history major at Oberlin. Before they came, he spoke to the executive director of the Kentucky Dems, who told him to come to Boston, go to the caucuses, and keep asking. Today he went to lunch with the Kentucky delegation, and twenty minutes later he had his pass.

“Our most important issue is the standing of America in the world. All the issues add up to, if we’re proud to say, traveling abroad, that we’re American. It’s tough to say that now.” They’re all concerned about the environment, too, says Joe.

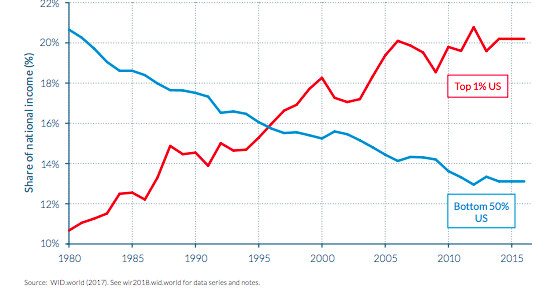

![]() Katie worries about the growing divide between upper and lower classes. “We don’t need the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer.” Also, “the attempt to put a gay marriage ban into the Constitution is just disgusting and unnecessary. It’s an attack on every American’s rights.”

Katie worries about the growing divide between upper and lower classes. “We don’t need the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer.” Also, “the attempt to put a gay marriage ban into the Constitution is just disgusting and unnecessary. It’s an attack on every American’s rights.”

Laura’s ex-boyfriend is a Marine. “I have so many friends that are serving overseas,” she says. “We’re losing too many people over there and I want it to be over as quickly as possible.”

They all agree that the deficit is a problem too, “that we’ll be paying back, and our kids,” Katie says.

They get out at my subway stop, planning to walk the two miles to Tufts in spite of Laura’s headache and the pouring rain. I hail a taxi and drop them off at the dorm instead. I feel like Mother Theresa.

Thursday night, July 29, 2004, the last night of the convention

I know the ropes by now. I eat my supper from a takeout bag, sitting on a tarp-covered box outside the security tents. So far the only money I’ve spent inside the FleetCenter is on phone calls. I might be the only media person here without a cell phone.

![]() Water inside the arena goes for $3.50 a bottle. Most people are in too much of a hurry to notice the two tents just inside the entry area where corporate sponsors are handing out free bottles of water and, Allah be praised, really amazing fruit smoothies. I always score a couple of the mango smoothies before I go inside.

Water inside the arena goes for $3.50 a bottle. Most people are in too much of a hurry to notice the two tents just inside the entry area where corporate sponsors are handing out free bottles of water and, Allah be praised, really amazing fruit smoothies. I always score a couple of the mango smoothies before I go inside.

Tonight, of course, the place is packed to the rafters. I find a seat in the nosebleed area, but it’s too hot and stuffy up here. I get tired of fanning myself with my plastic-wrapped press pass. We can’t see the stage anyway. There are television screens mounted near the ceiling for sports events, but they’re all dark for some reason.

The big screen is behind the podium, so the TV networks and the swing state delegations have the best view of it. Tonight I’m determined to actually listen to a bunch of speeches, like all these other poor slobs. I perch on a ledge in the writing press area and try to focus. The guy next to me, a syndicated radio talk show host in a yarmulke, is working on an article on parenting on his laptop. He says that people aren’t made to sit still for this stuff four days in a row. He’s ready to slam his head into a wall.

My resolve withers. Somehow I’ve missed Obama’s speech. He was such a hit, I’ll have to read the hard copy later. The rest of the speakers are all saying fine things, but they tend to be the same things everyone else is saying. Pretty soon I’m feeling, Okay! I’ll vote for Kerry! Shut up now please!

Fortunately we arrive at a musical interlude. Flags have been distributed so people can wave them for Willie Nelson’s intro. He sings with a big purple-robed choir. Three people in the press area are swaying to the music, but I’m getting sixtied-out, myself. I’ve heard Carole King and Peter, Paul, and Mary, but managed to miss all the musical acts I’d actually like to hear, like Wyclef Jean and the Black-Eyed Peas.

Max Cleland snaps me back to attention. He lost both legs and an arm fighting in Vietnam, and still the Republicans managed to paint him as soft on defense so he lost his re-election bid for Congress in Georgia. The Dems have given him a prime spot, introducing Kerry and his “band of brothers”, a phrase I will be heartily sick of in an hour or two.

Cleland sobers the crowd, grounds it, then seems to lift it up again. He’s not a grand orator. He just seems…real.

I head for the third level media info area before Kerry takes the stage. I’m surprised security lets me by. Maybe I’m flying under the radar at this point. Sometimes it’s good to be short.

Inside the info room, where dozens of media drones are filing their copy on laptops, a ragtag bunch of reporters, mostly very young, are sitting on the floor watching the speeches on television. The closed captions are quite entertaining. I especially like “I am here today through the graves of a higher being.”

I’m fascinated by Kerry’s daughter Alexandra’s speech. Did we really need the image of her father giving CPR to a hamster?

![]() One of the young reporters notes that the theme of trees seems to run through the Kerry family speeches. Kerry’s mother taught him that “trees are the cathedrals of nature”. There he is in the video, climbing a tree. When his daughter speaks of him making a little wire sculpture with autumn leaves on it for his dying mother, a very sweet story, we look at one another with raised eyebrows. Again with the trees! Are we going to have a pagan for president?

One of the young reporters notes that the theme of trees seems to run through the Kerry family speeches. Kerry’s mother taught him that “trees are the cathedrals of nature”. There he is in the video, climbing a tree. When his daughter speaks of him making a little wire sculpture with autumn leaves on it for his dying mother, a very sweet story, we look at one another with raised eyebrows. Again with the trees! Are we going to have a pagan for president?

I go back up the hall to where it opens onto the floor, and squeeze in by the temporary railing to watch the end of the show. Here come the balloons, red, white and blue, large, extra-large, and super-sized. They shower down in spurts, accompanied by a blizzard of confetti in the patriotic color scheme.

Many of the big net tubes by the ceiling that have been holding the balloons for this moment seem to be holding them still. Oops. Actually this is probably just as well, because even with a fraction of the balloons falling, the ground is covered with the things. They slide around, trip people, and pop with little explosions that must be nerve-wracking for security.![]()

I guess that’s all the excitement I can stand for the evening and walk out to the subway a few blocks away. The moon shines down on the departing crowd. In two days it will be full, the second full moon in July – what is called a blue moon. This seems appropriate, since once in a blue moon is how often the Dems are this unified.

There’s a middle-aged, fussy-looking little woman in the T station with a small white dog on a leash. She is oblivious to the fact that the dog is weaving around at the end of the leash, straining to greet every person it sees whether they want to play or not, making people stop short to keep from stepping on it.

This woman walks up to a policeman and talks to him for several minutes. It looks to me like she’s obeying the constant refrain on the T’s loudspeakers: “If you see or hear anything suspicious, no matter how small, report it to the authorities.”

Now I wish I’d gone up to the policeman right after she left him, to report an annoying woman and her annoying little dog.

Postscript

My friend JB, a generous soul, has allowed a couple of dozen protesters from out of town to camp on her suburban lawn. I talk with two of them on the phone after the convention is over, as they’re preparing to scatter to their home states, trying to find the key to unlock their bicycles, and so on.

Most of the protesters disdained to enter the protest pen, opting instead to perform random acts of spontaneous political expression around town. This strategy made it difficult to catch them in the act. I’m curious to hear what I missed.

Chris tells me he’s been a “freelance activist” since Sept. 11, 2001. He left a master’s program in history for this career, living now on small inheritances from his mother and grandmother, plus the occasional part-time job.

At a protest march last Saturday, two Boston policemen approached him and a friend and engaged them in conversation. He thinks this was a ruse, to keep them from interfering while two plainclothes officers whisked away a young Southeast Asian man standing nearby. Chris heard they released this guy a few hours later after questioning him because “he looked suspicious.”

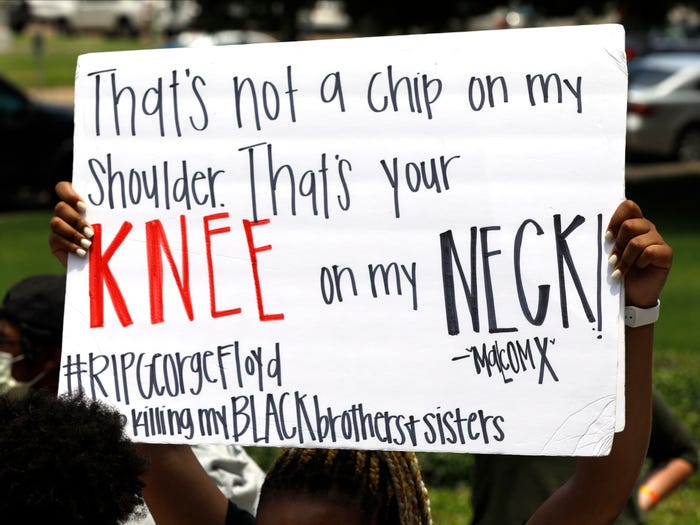

On Wednesday, a group of activists went to the protest pen to stage some street theater on the theme of Abu Ghraib. Some wore orange suits. Other activists pretended to arrest them, put them in pens, made them kneel, and put bags over their heads.

Chris says they didn’t have much of an audience besides the folks in real uniforms, but one black man who had just gotten out of the military joined the demonstration. “He’d been getting frustrated, but he was keeping his mouth shut. Now he says he’ll be protesting at the RNC.”

Chris notes that the protesters got thumbs-up from some of the police. The officers didn’t intervene when they burned an effigy with a Bush face on one side of its head and a Kerry face on the other. But when Chris started to pour some water into several smaller bottles, six policemen came right over. He drank some of the water to show them he wasn’t making incendiary devices.

I also speak with Jade, which is not his real first name but a nom de protest. Jade’s been a full-time activist for eight years, since he was 15 years old. He tells me he’s already been arrested 36 times. He’s with a group now called Pirates Against Bush. They wear pirate costumes and masks, and it sounds like they have a great time.

On Sunday, the Pirates couldn’t stay with the main anti-war march because the police wouldn’t let their bikes into the “soft” zone outside the protest pen. Instead they lay in the grass on the Common, pointing rude signs at the black helicopters overhead.

On Wednesday, Jade made himself a popular guy at a Pirate party after he talked a store manager out of several pounds of Godiva chocolates.

The Pirates did a lot of drumming on buckets this week, hassling television news teams by making noise behind the cameras. They staged mock sword fights and taunted the LaRouche people, chanting: “Are you cold? Burn the rich! Are you hungry? Eat the rich!” And other even less savory suggestions.

The fun and games got less fun at one point. It isn’t clear to me from Jade’s account exactly what happened. My husband says he saw a news report that blamed a molotov cocktail made out of paper mache. At any rate, as Jade says, “the craziness started.” He got hit in the back of the head with a nightstick, and got beaten some more when he tried to stop the police from grabbing another Pirate.

Jade saw police shove one young woman’s face onto the pavement so hard her nose was bleeding. He himself suffered a broken pinkie. He thinks three activists were arrested. A friend of his overheard some member of the SWAT team point at Jade and say, “I want him too,” so he told Jade to “run like hell,” which advice he took. An hour and a half later, when he called his sister in North Carolina, she said policemen had just visited their house, asking her to let them know when Jade returned.

Homeland Security seems to be keeping the world safe from Pirates. Jade won’t be going home anytime soon. He’ll hit a few other states and then be in New York at the end of August for the Republican convention.

Jade says he wonders why “outsider youth” like him and his friends seem so much happier than their more mainstream peers. “Part of it is the freedom of our imaginations,” he surmises. “Also, we’re never bored. We see things other people ignore, and they entertain us. They make us laugh.”

I forget to ask him if he’d noticed the Falun Gong.